Racial Science on the Frontiers of Hitler's Europe

Alongside the theme of modernity, the subject of racial exclusion rests at the center of the now voluminous scholarship dedicated to the Third Reich. In particular, hundreds, if not thousands, of studies have investigated the caustic forms of racial science, which undergirded Nazi ideology and provided the rationale for Adolf Hitler's regime's murderous and utopian efforts to restructure Europe demographically. Yet surprisingly little is known about the ways in which Nazi racial thinking interacted with local state and parastatal institutions in the German occupied territories, not to mention among the Reich's allies.

This collection of thirteen essays edited by Anton Weiss-Wendt and Rory Yeomans seeks to close this important historiographical gap. Originating in papers given at a conference on racial science held at the Center for the Study of the Holocaust and Religious Minorities in Oslo, Norway, the work is consciously comparative in nature. Jettisoning the traditional narrative of a top-down imposition from Berlin, the anthology instead refreshingly seeks to problematize the relationship between Germany and its vassal and satellite states concerning racial policy. Spanning the breadth of Nazi Europe, from the Netherlands and Norway to Italy, Romania, and the Baltic states of Estonia and Latvia, the essays highlight the ways in which eugenicists and ethnographers not only adhered to the tenets of Nazi racial doctrine but also subverted or challenged them in order to pursue agendas aimed at strengthening the body politic in their own countries.

As several essays in the volume note, the often complicated wartime relationship between European racial scientists and their Nazi counterparts stemmed from the fact that throughout the interwar period Germany played a key role in the development of racial science. Having emerged as an academic discipline in the early 1900s, the field was well established in the country by the 1930s, and research institutions at universities, such as Munich and Giessen, attracted students from as far away as Italy, Romania, and the Baltics eager to learn about the benefits of racial hygiene from some of the most prestigious scholars in the field. Indeed, eugenicists in east central Europe's fledgling new republics were especially keen to promote practices advocated in Germany, such as birth control and sterilization, as they appeared to offer the best means of navigating the social and economic pitfalls of the unstable interwar period.

Despite their admiration for the central role that eugenics played inside Germany after 1933, the authors highlight the considerable and enduring differences between these racial scientists and their German colleagues. As Isabel Heinemann notes in her incisive essay on the activities of the Reich Settlement Main Office (RuSHA), "seduced by abundant research funding and the prospect of swift national revival," many German academics enthusiastically implemented the regime's increasingly exclusionary racial policies (p. 50). Using the case study of RuSHA's activities in occupied Poland as a backdrop, the essay reveals that these racial specialists not only helped draft legislation, but also proved willing to go abroad as Nazism's racial vanguard after the outbreak of war in 1939, overseeing the deportation and extermination of non-Germans. Drawing on the rich historiography of Täterforschung, Heinemann conclusively demonstrates that these "architects of extermination" formed a distinct type of perpetrator, who, much like the counterpart in the Reich Security Main Office, was equally comfortable taking part in operations in the field as managing violent population transfers from offices in Berlin (p. 48). While readers familiar with Heinemann's previous work ("Rasse, Siedlung, deutsches Blut": Das Rasse-und Siedlungshauptamt der SS und die rassenpolitische Neuordnung Europas [2003]) will not find much new in terms of content, the essay serves an important function by setting up the juxtaposition between these Nazi racial scientists unconditionally committed to the violent pursuit of a racially pure Volksgemeinschaft and their often much less radical European contemporaries featured in subsequent essays.

The Nazis' uncompromising dedication to exclusionary racial ideology is further driven home in the keen contribution of Amy Carney. Fully intending the SS to serve not only as the martial arm of the German nation but also as an eternal wellspring of racially pure Nazi acolytes, throughout the war years, Heinrich Himmler took great pains to balance the tension between the burdens of frontline service and the need to ensure a demographic future for Nazism's racial elite. Unable to forego the necessity of providing valuable Menschenmaterial for the battlefield, the SS chief sought to encourage procreation by offering material incentives, reducing the bureaucratic red tape related to marriage applications, and even providing brief conjugal vacations for SS men. However, as Carney points out, these programs ironically cut against the grain of Himmler's vision of an ideal SS code, as the Reichsführer was dismayed to discover that most SS officers failed to grasp the importance of their reproductive obligations, and often simply reveled in the brief respite from frontline service.

The twisted nature of Nazi ethics is further astutely elaborated on by Wolfgang Bialas. Echoing the recent work of Alon Confino (Foundational Pasts: The Holocaust as Historical Understanding [2011]) and Raphael Gross (Anständig geblieben: Nationalsozialistische Moral [2012]), Bialas emphasizes the regime's efforts to supplant the Judeo-Christian humanist tradition with a new set of values that reflected National Socialism's view of history as a merciless life or death struggle between competing races by creating rigid binaries of belonging and exclusion. Citing as evidence the lack of apparent remorse among Nazi perpetrators during the postwar period and the often heard refrain that one was simply "following orders," he finds that the regime was largely successful in its attempt to provide justification for mass murder, reducing heinous crimes to mundane concepts, such as "work" or "duty," clinical terminology that revealed the lack of empathy for Nazism's victims and allowed killers to consider themselves, as Himmler remarked in his infamous Posen speech of 1943, "decent" guardians of the German racial community.

When placed alongside Nazism's ideological warriors, other European racial thinkers pale in comparison. Indeed, most eschewed violent schemes of racial purification, and others continued to adhere to competing conceptions of race, offsetting the hegemony of Nazi doctrine. For example, in Italy, eugenicists influenced by Latin and Catholic culture were more apt to promote positive eugenic policies, such as good hygiene and better working conditions, rather than resort to birth control or sterilization. The majority also tended to shy away from discussions of racial purity, instead using the term stirpe, or stock, to describe a national fusion of peoples that created a distinct, if superior, Mediterranean people. Indeed, throughout the 1920s and early 1930s, racial anti-Semitism and notions of pure races along the lines of those advocated by German academics remained relegated to the shadowy margins of racial discourse. However, things began to change after the Italian invasion of Abyssinia in 1935, which proved to be a turning point in Fascist thinking regarding race. This quest for empire demanded that Benito Mussolini's regime take a more concrete approach to such questions, as reflected in the discriminatory laws passed in Italy that barred sexual relationships between Italians and Africans in 1936. Another sign of the growing shift in discourse came two years later in the form of Guido Landra's 1938 "Race Manifesto," which advocated biological forms of anti-Semitism, and demanded expulsion of Italian Jews as irredeemable ballast. However, many of the ideas espoused in this document remained contentious, and heated debates between the national and biological camps of Italian racial science continued to rage until roughly 1943, when the formation of the Salo Republic, and more direct forms of German influence, definitively shifted the discourse in favor of racial biology.

The field of eugenics followed similar trajectories in southeastern Europe, where national belonging continued to be defined in anthropological and cultural terms until the 1940s. It was during this period that states allied to Nazi Germany acquired new territories, forcing reconsiderations of race. As Marius Turda points out in his case study of Hungary, "during the Second World War racial science acquired renewed importance in the public imagination," highlighting the critical role that the conflict played in radicalizing perceptions of the nation (p. 238). Characterized by tension between competing cultural and biological conceptions, few Hungarian racialists argued for a homogenous race until roughly 1938, when these debates were used to pursue territorial claims in southern Slovakia and Transylvania. Much like their German counterparts, flush with state funding, Hungarian eugenicists proved exceptionally willing to turn their research toward political ends, crafting a "Magyar race," which evidenced common hereditary characteristics, with predictable repercussions for the country's ethnic minorities. In neighboring Romania, racial thinkers were deeply troubled by the alleged dilution of the middle strata of society by the influx of foreigners, particularly Jews, who arrived from regions annexed after World War I. Inspired by German racial science, they sought to recast ethnicity, or neam, in biological terms, while remaining true to the idea of a synthesis of peoples which dominated Romanian national mythology. While they acknowledged that neam was created by centuries of ethnic fusion and argued against the conceptions of racial purity that dominated German racial science, they also warned that the Romania nation was now characterized by its "blood relationship," in which all its members shared in a common ancestry and needed to guard against the corruption of outside forces, namely, Jews. Thus, by 1942, Romanian racial scientists had created a "biologically hardened ethnic nationalism" that encouraged violence against outsiders (p. 279).

As Yeomans demonstrates, the country that adopted a racial doctrine most in tandem with that of Nazi Germany was the Independent State of Croatia. However, despite consciously modeling their policies on those practiced in the Third Reich, Ustasha racism cut an erratic course contingent on both changing leadership and a host of other factors that justified both atrocity and softer forms of discrimination. These contradictions were best exposed by the discourse surrounding the initial main target of the Ustasha, the Serbs. In contrast to the Jews and Roma, who were classified as racial outsiders and sanctioned by legislation that prevented them from interacting with "Aryans," Serbs never became the target of racial laws, and although the media constantly trumpeted the need for Croats to protect their racial purity, marriage with Serbs was never banned. Instead they were targeted for a campaign of cultural destruction alongside the murder operations carried out by Ustasha death squads. In the face of widespread Serbian resistance and a changing of the guard to a more moderate Ustasha leadership, by 1942 the regime had largely begun to abandon mass violence in favor of temporary, forced assimilation. During this period, Croatian eugenicists backpedaled from their earlier project of providing justification for the murder of the Serbian population. However, they still played an influential role in shaping doctrine by arguing that the minority needed to be purged of its intelligentsia and clergy, as they constituted the core of the Serb nation. By September 1944, as a new, radical leadership took the helm, Croatian racial scientists again found themselves espousing racist rhetoric against the Serbs, as the regime undertook one last effort to wipe them out. By astutely charting the ebb and flow of mass violence, Yeoman's essay dovetails neatly with the assertions of Christian Gerlach (Extremely Violent Societies: Mass Violence in the Twentieth-Century World [2010]) and Alexander Korb (Im Schatten des Weltkrieges: Massen Gewalt der Ustaša gegen Serben, Juden und Roma in Kroatien 1941-1945 ([2013]) by highlighting the often erratic and uncontrollable nature of atrocity. By doing so, Yeoman refreshingly departs from the well-established scholarly interpretations regarding the state's monopoly, or lack thereof, on the course and scope of ethnically motivated violence.

In other parts of Europe, racial scientists tried to align their field with Nazi doctrine in order to work through the occupation, toward the end of strengthening their own national composition. This was the case in Estonia, where Weiss-Wendt finds that the ethnographers who formed the backbone of the nationalist movement were eager to work with Nazi authorities. During the interwar period, Estonian eugenicists faced what they perceived to be a demographic crisis motivated by a growing Russian minority. They eagerly seized on the opportunity to work with Nazi security forces to remove this allegedly threatening demographic segment, and successfully lobbied for the repatriation of the Estonian minorities inside the occupied Soviet Union, mirroring the Nazis' own efforts to repatriate ethnic Germans. While Hitler's regime came to view Estonia as an advance base for a racially restructured new Europe, in a certain sense, Weiss-Wendt finds that the tail wagged the dog, as local eugenicists sought to consolidate and bolster the nation through collaboration, working through intellectual, material, and security resources offered by the Nazis.

The apparent benefits of siding with the Germans are also found in Geraldien von Frijtag Drabbe Künzel's piece on Dutch settlers in the Nazi East. Traditionally, Dutch eugenicists had looked to Netherlands' colonies in Southeast Asia as a pressure valve to release "surplus" segments of the population and prevent a drain of resources inside the metropole. With Indonesia and parts of New Guinea occupied by Japanese troops, Dutch eugenicists eagerly seized on the opportunities offered by the Germans to promote settlement in Belarus and Ukraine. Between 1941 and 1944, 5,216 Dutch "pioneers" trekked eastward to farm plots of fertile black soil promised to them by the Nazi regime. They soon found that life in the East was double edged--while they were given free rein to command and exploit the "racially inferior" Slavs, they also quickly discovered the startling absence of racial comradeship exhibited by the Germans. Disdained as black marketeers, crooks, and "white Jews" by the Germans, the Dutch discovered they fit uncomfortably low within the racial hierarchy of the East, a fact that cruelly debunked the myth of Germanic kinship touted by the Nazi and Dutch governments inside the metropole.

This comprehensive and diverse volume succeeds in its intention to fill an important historiographical gap and challenge the hegemony of Nazi racial thinking inside Hitler's Europe. The one glaring weakness is the absence of an essay on France. Given the country's contribution to the racial reordering of Western Europe, not to mention the still controversial subject of Vichy collaboration, such a contribution would have rounded out the anthology. Likewise, an effort to compare the eugenic and racial policies of Nazi Europe with those of the neutral states of Switzerland and Sweden might have added further weight to the overarching theme of the work.[1] Lastly, an essay that discussed the effects of these racial policies at ground level or from the perspective of their victims would also have been welcome. While engaging and important, the majority of the chapters, with the notable exception of Yeoman's piece on Croatia, fail to break out of the realm of intellectual history and consider how these ideas played out once they were put into action. Such an investigation would have added a further layer of problematization, demonstrating the contradictions between racial theory and practice that not only allowed for mass violence and discrimination but also showed how targeted groups were in some rare cases, even if only momentarily, spared the full brunt of eliminationist eugenic policies. Here the plight of half-Jewish Germans springs readily to mind, a case which demonstrates that even at the heart of Nazism, cracks and fissures in racial thinking remained, allowing space for survival.[2] These points aside, the anthology remains a refreshing, cohesive, and compelling contribution to the scholarship on racial policy inside Hitler's Europe.

McConnell on Weiss-Wendt and Yeomans, 'Racial Science in Hitler's New Europe, 1938-1945'

Author: Anton Weiss-Wendt, Rory Yeomans

Reviewer: Michael McConnell

Anton Weiss-Wendt, Rory Yeomans. Racial Science in Hitler's New Europe, 1938-1945. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2013. 416 pp. (paper), ISBN 978-0-8032-4507-5.

Reviewed by Michael McConnell (University of Tennessee-Knoxville)

Published on H-German (September, 2014)

Commissioned by Chad Ross

Notes

[1]. See Thomas Etzemüller, "Total aber nicht totalitär: Die schwedische Volksgemeinschaft," in Volksgemeinschaft: Neue Forschungen zur Gesellschaft des Nationalsozialismus, ed. Frank Bahjor and Michael Wildt (Frankfurt am Main: Fischer Verlag, 2009).

[2]. James F. Tent, In the Shadow of the Holocaust: Nazi Persecution of Jewish-Christian Germans (Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 2003).

Printable Version: http://www.h-net.org/reviews/showpdf.php?id=40388

Citation: Michael McConnell. Review of Weiss-Wendt, Anton; Yeomans, Rory, Racial Science in Hitler's New Europe, 1938-1945. H-German, H-Net Reviews. September, 2014.

URL: http://www.h-net.org/reviews/showrev.php?id=40388

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 United States License.

Source: H-Net

https://networks.h-net.org/node/35008/reviews/46331/mcconnell-weiss-wendt-and-yeomans-racial-science-hitlers-new-europe

Monday, February 15, 2016

Sunday, February 7, 2016

The System. Two new histories show how the Nazi concentration camps worked

| Prisoners break up clay for the brickworks at Sachsenhausen-Oranienburg, in 1939. Credit Photograph from Akg-Images |

Le Porz’s remark was prophetic. The true extent of Nazi barbarity became known to the world in part through the documentary films made by Allied forces after the liberation of other German camps. There have been many atrocities committed before and since, yet to this day, thanks to those images, the Nazi concentration camp stands as the ultimate symbol of evil. The very names of the camps—Dachau, Bergen-Belsen, Buchenwald, Auschwitz—have the sound of a malevolent incantation. They have ceased to be ordinary place names—Buchenwald, after all, means simply “beech wood”—and become portals to a terrible other dimension.

To write the history of such an institution, as Nikolaus Wachsmann sets out to do in another new book, “KL: A History of the Nazi Concentration Camps” (Farrar, Straus & Giroux), might seem impossible, like writing the history of Hell. And, certainly, both his book and Helm’s are full of the kind of details that ordinarily appear only in Dantesque visions. Helm devotes a chapter to Ravensbrück’s Kinderzimmer, or “children’s room,” where inmates who came to the camp pregnant were forced to abandon their babies; the newborns were left to die of starvation or be eaten alive by rats. Wachsmann quotes a prisoner at Dachau who saw a transport of men afflicted by dysentery arrive at the camp: “We saw dozens . . . with excrement running out of their trousers. Their hands, too, were full of excrement and they screamed and rubbed their dirty hands across their faces.”

These sights, like the truck full of bodies, are not beyond belief—we know that they were true—but they are, in some sense, beyond imagination. It is very hard, maybe impossible, to imagine being one of those men, still less one of those infants. And such sights raise the question of why, exactly, we read about the camps. If it is merely to revel in the grotesque, then learning about this evil is itself a species of evil, a further exploitation of the dead. If it is to exercise sympathy or pay a debt to memory, then it quickly becomes clear that the exercise is hopeless, the debt overwhelming: there is no way to feel as much, remember as much, imagine as much as the dead justly demand. What remains as a justification is the future: the determination never again to allow something like the Nazi camps to exist.

And for that purpose it is necessary not to think of the camps simply as a hellscape. Reading Wachsmann’s deeply researched, groundbreaking history of the entire camp system makes clear that Dachau and Buchenwald were the products of institutional and ideological forces that we can understand, perhaps all too well. Indeed, it’s possible to think of the camps as what happens when you cross three disciplinary institutions that all societies possess—the prison, the army, and the factory. Over the several phases of their existence, the Nazi camps took on the aspects of all of these, so that prisoners were treated simultaneously as inmates to be corrected, enemies to be combatted, and workers to be exploited. When these forms of dehumanization were combined, and amplified to the maximum by ideology and war, the result was the Konzentrationlager, or K.L.

Though we tend to think of Hitler’s Germany as a highly regimented dictatorship, in practice Nazi rule was chaotic and improvisatory. Rival power bases in the Party and the German state competed to carry out what they believed to be Hitler’s wishes. This system of “working towards the Fuhrer,” as it was called by Hitler’s biographer Ian Kershaw, was clearly in evidence when it came to the concentration camps. The K.L. system, during its twelve years of existence, included twenty-seven main camps and more than a thousand subcamps. At its peak, in early 1945, it housed more than seven hundred thousand inmates. In addition to being a major penal and economic institution, it was a central symbol of Hitler’s rule. Yet Hitler plays almost no role in Wachsmann’s book, and Wachsmann writes that Hitler was never seen to visit a camp. It was Heinrich Himmler, the head of the S.S., who was in charge of the camp system, and its growth was due in part to his ambition to make the S.S. the most powerful force in Germany.

Long before the Nazis took power, concentration camps had featured in their imagination. Wachsmann finds Hitler threatening to put Jews in camps as early as 1921. But there were no detailed plans for building such camps when Hitler was named Chancellor of Germany, in January, 1933. A few weeks later, on February 27th, he seized on the burning of the Reichstag—by Communists, he alleged—to launch a full-scale crackdown on his political opponents. The next day, he implemented a decree, “For the Protection of People and State,” that authorized the government to place just about anyone in “protective custody,” a euphemism for indefinite detention. (Euphemism, too, was to be a durable feature of the K.L. universe: the killing of prisoners was referred to as Sonderbehandlung, “special treatment.”)

During the next two months, some fifty thousand people were arrested on this basis, in what turned into a “frenzy” of political purges and score-settling. In the legal murk of the early Nazi regime, it was unclear who had the power to make such arrests, and so it was claimed by everyone: national, state, and local officials, police and civilians, Party leaders. “Everybody is arresting everybody,” a Nazi official complained in the summer of 1933. “Everybody threatens everybody with Dachau.” As this suggests, it was already clear that the most notorious and frightening destination for political detainees was the concentration camp built by Himmler at Dachau, in Bavaria. The prisoners were originally housed in an old munitions factory, but soon Himmler constructed a “model camp,” the architecture and organization of which provided the pattern for most of the later K.L. The camp was guarded not by police but by members of the S.S.—a Nazi Party entity rather than a state force.

These guards were the core of what became, a few years later, the much feared Death’s-Head S.S. The name, along with the skull-and-crossbones insignia, was meant to reinforce the idea that the men who bore it were not mere prison guards but front-line soldiers in the Nazi war against enemies of the people. Himmler declared, “No other service is more devastating and strenuous for the troops than just that of guarding villains and criminals.” The ideology of combat had been part of the DNA of Nazism from its origin, as a movement of First World War veterans, through the years of street battles against Communists, which established the Party’s reputation for violence. Now, in the years before actual war came, the K.L. was imagined as the site of virtual combat—against Communists, criminals, dissidents, homosexuals, Jehovah’s Witnesses, and Jews, all forces working to undermine the German nation.

The metaphor of war encouraged the inhumanity of the S.S. officers, which they called toughness; licensed physical violence against prisoners; and accounted for the military discipline that made everyday life in the K.L. unbearable. Particularly hated was the roll call, or Appell, which forced inmates to wake before dawn and stand outside, in all weather, to be counted and recounted. The process could go on for hours, Wachsmann writes, during which the S.S. guards were constantly on the move, punishing “infractions such as poor posture and dirty shoes.”

The K.L. was defined from the beginning by its legal ambiguity. The camps were outside ordinary law, answerable not to judges and courts but to the S.S. and Himmler. At the same time, they were governed by an extensive set of regulations, which covered everything from their layout (including decorative flower beds) to the whipping of prisoners, which in theory had to be approved on a case-by-case basis by Himmler personally. Yet these regulations were often ignored by the camp S.S.—physical violence, for instance, was endemic, and the idea that a guard would have to ask permission before beating or even killing a prisoner was laughable. Strangely, however, it was possible, in the prewar years, at least, for a guard to be prosecuted for such a killing. In 1937, Paul Zeidler was among a group of guards who strangled a prisoner who had been a prominent churchman and judge; when the case attracted publicity, the S.S. allowed Zeidler to be charged and convicted. (He was sentenced to a year in jail.)

In “Ravensbrück,” Helm gives a further example of the erratic way the Nazis treated their own regulations, even late in the war. In 1943, Himmler agreed to allow the Red Cross to deliver food parcels to some prisoners in the camps. To send a parcel, however, the Red Cross had to mark it with the name, number, and camp location of the recipient; requests for these details were always refused, so that there was no way to get desperately needed supplies into the camps. Yet when Wanda Hjort, a young Norwegian woman living in Germany, got hold of some prisoners’ names and numbers—thanks to inmates who smuggled the information to her when she visited the camp at Sachsenhausen—she was able to pass them on to the Norwegian Red Cross, whose packages were duly delivered. This game of hide-and-seek with the rules, this combination of hyper-regimentation and anarchy, is what makes Kafka’s “The Trial” seem to foretell the Nazi regime.

Cartoon

“And, as you drive, it will also use all the negative energy from your arguments.”

Buy the print »

Even the distinction between guard and prisoner could become blurred. From early on, the S.S. delegated much of the day-to-day control of camp life to chosen prisoners known as Kapos. This system spared the S.S. the need to interact too closely with prisoners, whom they regarded as bearers of filth and disease, and also helped to divide the inmate population against itself. Helm shows that, in Ravensbrück, where the term “Blockova” was used, rather than Kapo, power struggles took place among prisoner factions over who would occupy the Blockova position in each barrack. Political prisoners favored fellow-activists over criminals and “asocials”—a category that included the homeless, the mentally ill, and prostitutes—whom they regarded as practically subhuman. In some cases, Kapos became almost as privileged, as violent, and as hated as the S.S. officers. In Ravensbrück, the most feared Blockova was the Swiss ex-spy Carmen Mory, who was known as the Black Angel. She was in charge of the infirmary, where, Helm writes, she “would lash out at the sick with the whip or her fists.” After the war, she was one of the defendants tried for crimes at Ravensbrück, along with S.S. leaders and doctors. Mory was sentenced to death but managed to commit suicide first.

At the bottom of the K.L. hierarchy, even below the criminals, were the Jews. Today, the words “concentration camp” immediately summon up the idea of the Holocaust, the genocide of European Jews by the Nazis; and we tend to think of the camps as the primary sites of that genocide. In fact, as Wachsmann writes, as late as 1942 “Jews made up fewer than five thousand of the eighty thousand KL inmates.” There had been a temporary spike in the Jewish inmate population in November, 1938, after Kristallnacht, when the Nazis rounded up tens of thousands of Jewish men. But, for most of the camps’ first decade, Jewish prisoners had usually been sent there not for their religion, per se, but for specific offenses, such as political dissent or illicit sexual relations with an Aryan. Once there, however, they found themselves subject to special torments, ranging from running a gantlet of truncheons to heavy labor, like rock-breaking. As the chief enemies in the Nazi imagination, Jews were also the natural targets for spontaneous S.S. violence—blows, kicks, attacks by savage dogs.

The systematic extermination of Jews, however, took place largely outside the concentration camps. The death camps, in which more than one and a half million Jews were gassed—at Belzec, Sobibór, and Treblinka—were never officially part of the K.L. system. They had almost no inmates, since the Jews sent there seldom lived longer than a few hours. By contrast, Auschwitz, whose name has become practically a synonym for the Holocaust, was an official K.L., set up in June, 1940, to house Polish prisoners. The first people to be gassed there, in September, 1941, were invalids and Soviet prisoners of war. It became the central site for the deportation and murder of European Jews in 1943, after other camps closed. The vast majority of Jews brought to Auschwitz never experienced the camp as prisoners; more than eight hundred thousand of them were gassed upon arrival, in the vast extension of the original camp known as Birkenau. Only those picked as capable of slave labor lived long enough to see Auschwitz from the inside.

Many of the horrors associated with Auschwitz—gas chambers, medical experiments, working prisoners to death—had been pioneered in earlier concentration camps. In the late thirties, driven largely by Himmler’s ambition to make the S.S. an independent economic and military power within the state, the K.L. began a transformation from a site of punishment to a site of production. The two missions were connected: the “work-shy” and other unproductive elements were seen as “useless mouths,” and forced labor was a way of making them contribute to the community. Oswald Pohl, the S.S. bureaucrat in charge of economic affairs, had gained control of the camps by 1938, and began a series of grandiose building projects. The most ambitious was the construction of a brick factory near Sachsenhausen, which was intended to produce a hundred and fifty million bricks a year, using cutting-edge equipment and camp labor.

The failure of the factory, as Wachsmann describes it, was indicative of the incompetence of the S.S. and the inconsistency of its vision for the camps. To turn prisoners into effective laborers would have required giving them adequate food and rest, not to mention training and equipment. It would have meant treating them like employees rather than like enemies. But the ideological momentum of the camps made this inconceivable. Labor was seen as a punishment and a weapon, which meant that it had to be extorted under the worst possible circumstances. Prisoners were made to build the factory in the depths of winter, with no coats or gloves, and no tools. “Inmates carried piles of sand in their uniforms,” Wachsmann writes, while others “moved large mounds of earth on rickety wooden stretchers or shifted sacks of cement on their shoulders.” Four hundred and twenty-nine prisoners died and countless more were injured, yet in the end not a single brick was produced.

This debacle did not discourage Himmler and Pohl. On the contrary, with the coming of war, in 1939, S.S. ambitions for the camps grew rapidly, along with their prisoner population. On the eve of the war, the entire K.L. system contained only about twenty-one thousand prisoners; three years later, the number had grown to a hundred and ten thousand, and by January, 1945, it was more than seven hundred thousand. New camps were built to accommodate the influx of prisoners from conquered countries and then the tens of thousands of Red Army soldiers taken prisoner in the first months after Operation Barbarossa, the German invasion of the U.S.S.R.

The enormous expansion of the camps resulted in an exponential increase in the misery of the prisoners. Food rations, always meagre, were cut to less than minimal: a bowl of rutabaga soup and some ersatz bread would have to sustain a prisoner doing heavy labor. The result was desperate black marketing and theft. Wachsmann writes, “In Sachsenhausen, a young French prisoner was battered to death in 1941 by an SS block leader for taking two carrots from a sheep pen.” Starvation was endemic and rendered prisoners easy prey for typhus and dysentery. At the same time, the need to keep control of so many prisoners made the S.S. even more brutal, and sadistic new punishments were invented. The “standing commando” forced prisoners to stand absolutely still for eight hours at a time; any movement or noise was punished by beatings. The murder of prisoners by guards, formerly an exceptional event in the camps, now became unremarkable.

But individual deaths, by sickness or violence, were not enough to keep the number of prisoners within manageable limits. Accordingly, in early 1941 Himmler decided to begin the mass murder of prisoners in gas chambers, building on a program that the Nazis had developed earlier for euthanizing the disabled. Here, again, the camps’ sinister combination of bureaucratic rationalism and anarchic violence was on display. During the following months, teams of S.S. doctors visited the major camps in turn, inspecting prisoners in order to select the “infirm” for gassing. Everything was done with an appearance of medical rigor. The doctors filled out a form for each inmate, with headings for “Diagnosis” and “Incurable Physical Ailments.” But it was all mere theatre. Helm’s description of the visit of Dr. Friedrich Mennecke to Ravensbrück, in November, 1941, shows that inspections of prisoners—whom he referred to in letters home as “forms” or “portions”—were cursory at best, with the victims parading naked in front of the doctors at a distance of twenty feet. (Jewish prisoners were automatically “selected,” without an examination.) In one letter, Mennecke brags of having disposed of fifty-six “forms” before noon. Those selected were taken to an undisclosed location for gassing; their fate became clear to the remaining Ravensbrück prisoners when the dead women’s clothes and personal effects arrived back at the camp by truck.

Under this extermination program, known to S.S. bureaucrats by the code Action 14f13, some sixty-five hundred prisoners were killed in the course of a year. By early 1942, it had become obsolete, as the scale of death in the camps increased. Now the killing of weak and sick prisoners was carried out by guards or camp doctors, sometimes in gas chambers built on site. Those who were still able to work were increasingly auctioned off to private industry for use as slave labor, in the many subcamps that began to spring up around the main K.L. At Ravensbrück, the Siemens corporation established a factory where six hundred women worked twelve-hour shifts building electrical components. The work was brutally demanding, especially for women who were sick, starved, and exhausted. Helm writes that “Siemens women suffered severely from boils, swollen legs, diarrhea and TB,” and also from an epidemic of nervous twitching. When a worker reached the end of her usefulness, she was sent back to the camp, most likely to be killed. It was in this phase of the camp’s life that sights like the one Loulou Le Porz saw at Ravensbrück—a truck full of prisoners’ corpses—became commonplace.

By the end of the war, the number of people who had died in the concentration camps, from all causes—starvation, sickness, exhaustion, beating, shooting, gassing—was more than eight hundred thousand. The figure does not include the hundreds of thousands of Jews gassed on arrival at Auschwitz. If the K.L. were indeed a battlefront, as the Death’s-Head S.S. liked to believe, the deaths, in the course of twelve years, roughly equalled the casualties sustained by the Axis during the Battle of Stalingrad, among the deadliest actual engagements of the war. But in the camps the Nazis fought against helpless enemies. Considered as prisons, too, the K.L. were paradoxical: it was impossible to correct or rehabilitate people whose very nature, according to Nazi propaganda, was criminal or sick. And as economic institutions they were utterly counterproductive, wasting huge numbers of lives even as the need for workers in Germany became more and more acute.

The concentration camps make sense only if they are understood as products not of reason but of ideology, which is to say, of fantasy. Nazism taught the Germans to see themselves as a beleaguered nation, constantly set upon by enemies external and internal. Metaphors of infection and disease, of betrayal and stabs in the back, were central to Nazi discourse. The concentration camp became the place where those metaphorical evils could be rendered concrete and visible. Here, behind barbed wire, were the traitors, Bolsheviks, parasites, and Jews who were intent on destroying the Fatherland.

And if existence was a struggle, a war, then it made no sense to show mercy to the enemy. Like many Nazi institutions, the K.L. embodied conflicting impulses: to reform the criminal, to extort labor from the unproductive, to quarantine the contagious. But most fundamental was the impulse to dehumanize the enemy, which ended up confounding and overriding all the others. Once a prisoner ceased to be human, he could be brutalized, enslaved, experimented on, or gassed at will, because he was no longer a being with a soul or a self but a biological machine. The Muselmänner, the living dead of the camps, stripped of any capacity to think or feel, were the true product of the K.L., the ultimate expression of the Nazi world view.

The impulse to separate some groups of people from the category of the human is, however, a universal one. The enemies we kill in war, the convicted prisoners we lock up for life, even the distant workers who manufacture our clothes and toys—how could any society function if the full humanity of all these were taken into account? In a decent society, there are laws to resist such dehumanization, and institutional and moral forces to protest it. When guards at Rikers Island beat a prisoner to death, or when workers in China making iPhones begin to commit suicide out of despair, we regard these as intolerable evils that must be cured. It is when a society decides that some people deserve to be treated this way—that it is not just inevitable but right to deprive whole categories of people of their humanity—that a crime on the scale of the K.L. becomes a possibility. It is a crime that has been repeated too many times, in too many places, for us to dismiss it with the simple promise of never again.

By Adam Kirsch

2015_04_06

Source: The New Yorker

http://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2015/04/06/the-system-books-kirsch

Thursday, February 4, 2016

El franquismo pudo haber muerto en 1944 por “cuestión de horas”

| Adolf Hitler y Francisco Franco, durante su encuentro en Hendaya. |

A. GODOY | 03/02/2016

Se suele decir que el régimen de Franco fue muy hábil en política internacional durante la Segunda Guerra Mundial, siendo capaz de mantenerse neutral pero nunca dejando de mostrar su afinidad por la Alemania Nazi. En el momento que la derrota de Hitler se veía cada vez más cercana en Europa, se empezó a decidir el destino de Franco, pero no fue en España, sino entre las potencias aliadas.

Como ahora nos muestra el profesor Carlos Collado en su nuevo libro, El telegrama que salvó a Franco, no fue la habilidad del dictador, sino un simple cúmulo de circunstancias y desacuerdos, hasta ahora desconocidos, los que permitieron la supervivencia del último régimen fascista de Europa.

ELPLURAL.COM – El título del libro hace referencia al telegrama que se escribió, pero que al final no se envió desde el Gobierno inglés al estadounidense, aceptando su idea de una política económica represiva con el régimen franquista. ¿Cómo fueron estas horas que pudieron cambiar el destino de España desde el extranjero? ¿Por qué al final fueron los estadounidenses los que cedieron y no se envió el telegrama?

CARLOS COLLADO - La redacción de este telegrama se produce en el momento álgido de un durísimo enfrentamiento entre Londres y Washington acerca de la política a seguir respecto a la de España de Franco. El Gobierno estadounidense estaba harto de que aún en 1944 Franco siguiera haciendo votos de amistad en sus relaciones con el régimen nazi y continuara suministrando materias primas imprescindibles para la industria bélica del Tercer Reich. Con este telón de fondo, los americanos impusieron un embargo de productos petrolíferos, que mantenían a flote la economía española, con el fin de subyugar a un Régimen que era considerado netamente como fascista.

Londres, por su parte, abogaba por un compromiso consensuado con Madrid, para de esta forma no arriesgar la provocación de una situación violenta e incontrolable en España. Los británicos confiaban en una transición pacífica hacia una restauración monárquica en la persona de Don Juan.

| Portada del nuevo libro de Carlos Collado – Editorial |

Ni siquiera un apremiante intercambio de telegramas al más alto nivel político, es decir entre Roosevelt y Churchill, logró acortar las distancias existentes. Finalmente, Churchill, instado por su ministro de Exteriores Anthony Eden, optó por retractarse para no llegar a una situación de ruptura. Pero antes de que se despachara dicho telegrama, llegó otro desde Washington, clasificado como urgentísimo, que anunciaba que los americanos por su parte se plegaban ante la insistencia mostrada por los británicos. Washington consideró a su vez que era preferible no romper públicamente con Londres en esta cuestión. De hecho, aquel día 25 de abril de 1944 se jugó el futuro del Régimen. Se trató de una cuestión de horas. Tal y como relatan observadores, en aquel momento se perdió una oportunidad única para deshacerse de un régimen considerado como fascista.

P – Tras el episodio del telegrama. La idea de los ingleses, encabezada por su embajador en Madrid, era promover una evolución pacífica del régimen para restaurar la monarquía. En el libro habla de las conversaciones del embajador con los sectores monárquicos españoles. ¿Conocía Don Juan las intenciones de los ingleses? ¿Cómo fue evolucionando su opinión con respecto a éstas?

C.C - Don Juan, después de una fase en la que parece haber estado acariciando la idea de lograr la restauración con la ayuda de las potencias del Eje, se volcó finalmente del lado de los ingleses. No caben dudas de que estaba al tanto y aprobaba lo que estaban tramando confidentes suyos, como su representante en España, el infante Alfonso de Orleans.

Él mismo anhelaba que el Gobierno británico se decidiera a apoyar su causa abiertamente. A este respecto incluso lanzó personalmente diversas iniciativas, sea en el contexto del funeral en honor de Beatriz de Battenberg, al que asistió su madre, o finalmente, a través del Manifiesto de Lausana a mediados de marzo de 1945. Éste contenía un anuncio de libertades y plenos derechos en el caso de que se restaurase la monarquía en su persona, dirigido, obviamente, a la opinión pública británica y estadounidense.

Pero mientras que el embajador británico Samuel Hoare persiguió una ambición personal, incluso a espaldas de su Gobierno, de entrar en la historia como el personaje que lograra derribar a Franco, el Gobierno de Londres no estaba dispuesto a sacarle a Don Juan las castañas del fuego.

Por otra parte, el contenido del Manifiesto de Lausana causó espanto entre los seguidores del pretendiente al trono, pues en la Guerra Civil habían cerrado filas alrededor de Franco precisamente en contra de esas libertades anunciadas por Don Juan. A fin de cuentas, los monárquicos estaban altamente satisfechos con la situación privilegiada que gozaban con Franco.

P – Con respecto a la relación de España con la Alemania de Hitler ¿En qué momento se empezó a distanciar el régimen franquista del nazi? ¿Y cómo fue visto esto desde EEUU y Reino Unido?

C.C – El régimen de Franco se aferró a la amistad con Berlín haste el último momento, e hizo todo lo que estaba a su alcance para apoyar su causa. Si bien tuvo que corregir ciertas medidas que violaban clarísimamente sus obligaciones como país neutral, ni siquiera se cumplieron los acuerdos con los Aliados: la retirada de la División Azul fue contrarrestada – al menos por un tiempo – por la creación de la Legión Azul; el embargo de las exportaciones de materiales estratégicos fue seguido por un tráfico clantestino que incluso superó lo que se había suministrado anteriormente; el compromiso de acotar el espionaje alemán no se cumplió en ningún momento de forma significativa, sino que los agentes siguieron gozando de gran libertad de acción.

Además, se mantuvo hasta abril de 1945 la ruta aérea de la Lufthansa, con lo que los nazis siguieron lloviendo en el territorio español hasta el último momento. Y aun después de la capitulación del Reich se permitió la entrada clandestina y dio cobijo a nazis que eran requeridos por las potencias de ocupación.

Londres y Washington reaccionaron completamente perplejos ante lo que consideraban que era no querer ver que el fascimo estaba condenado a desaparecer.

P – ¿Por qué la diplomacia española quiso, tras el fin de la II Guerra Mundial, mantener sus relaciones amistosas con Alemania si, como afirma en el libro, esto solo mantendría la apariencia de España como régimen fascista?

C.C – Franco, además de afinidades ideológicas, quiso distinguirse como el último amigo del Tercer Reich, para de esta forma poder ser el primer amigo de la Alemania de postguerra. Franco partía de la convicción de que Alemania seguiría siendo en todo momento una gran potencia europea, con lo que la demostración de una amistad inquebrantable en una situación en la que ya no le quedaban aliados, redundaría en tener a un valedor en la postguerra.

Carlos Collado es profesor de historia en la Universidad contemporanea en la Universidad de Marbug (Alemania)

Carlos Collado es profesor de historia en la Universidad contemporanea en la Universidad de Marbug (Alemania)

Además, Franco estuvo convencido hasta poco menos que el final de la guerra de que los Aliados finalmente entrarían “en razón” y firmarían un armisticio con el régimen nazi, para arremeter en contra de lo que él consideraba que era el real peligro para la paz mundial: la Unión Soviética.

Esto eran planteamientos fundamentalmente erróneos que, en abril de 1944, por poco hubieran tenido consecuencias catastróficas para Franco.

P – Por último, llama mucho la atención la aparición en el libro de la figura de José Antonio Aguirre, presidente del Gobierno vasco en el exilio, y que fue propuesto por el director de la inteligencia militar estadounidense para sustituir a Franco. ¿Cómo fue recibida esta propuesta por el Gobierno de EEUU? ¿Se dio a conocer a los británicos?

C.C - El Jefe del OSS, William Donovan, estaba convencido del gran daño que causaría la pervivencia del Régimen a los intereses nacionales estadounidenses, y apostaba por Aguirre porque éste había trabajado estrechamente con su organización poniendo a su disposición su red de agentes. Aguirre, además no solo gozaba de buena reputación entre los grupos del exilio republicano, sino que estaba trabajando para lograr una unidad de acción.

En el Departamento de Estado norteamericano se compartía la convicción de que la pervivencia del Régimen era un gran lastre, pues con ello no se cumpliría la misión por la que se habían empuñado las armas. Pero por una parte, en aquel momento aún no había cuajado la razón de ser de la intervención en los asuntos internos de países con los que se mantenían relaciones diplomáticas; pero sobre todo no se creía que precisamente un nacionalista vasco fuera la persona indicada para liderar un movimiento a nivel nacional.

Dado que en los asuntos de los servicios secretos existía un determinado secretismo entre las potencias aliadas, sobre todo si se trataba de operaciones que contravenían el derecho internacional, es más que dudoso que los británicos hayan sido informados de forma oficial. Otra cosa, sin embargo, es el hervidero de rumores que representaba el Madrid de aquellos días.

Source: El Plural (España)

http://www.elplural.com/2016/02/03/el-franquismo-pudo-haber-muerto-en-1944-por-cuestion-de-horas/#

Tuesday, February 2, 2016

Adam TOOZE. Le Salaire de la destruction. Formation et ruine de l’économie nazie

Adam TOOZE. Le Salaire de la destruction. Formation et ruine de l’économie nazie

Paris, Les Belles Lettres, 2012, 812 p.

dimanche 3 mars 2013, par Laurent Gayme

Diplômé de King’s College et de la London School of Economics, Adam Tooze enseigne l’histoire de l’Allemagne à l’Université de Yale. Il a déjà publié Statistics and the German State, 1900-1945 : The Making of Modern Economic Knowledge, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 2001. Cet ouvrage est la traduction de son livre The Wages of Destruction : The Making and Breaking of the Nazi Economy, London, Allen Lane, 2006, récompensé la même année par le Wolfson History Prize et en 2007 par le Longman-History Today Book of the Year Prize.

Remettre l’histoire économique au centre

Il faut saluer cette traduction, que nous proposent Les Belles Lettres, d’un livre majeur. Le lecteur français a pu lire, ces dernières années, de nombreux ouvrages novateurs sur l’Allemagne nazie, qu’il s’agisse de ceux de Ian Kershaw, de Robert Gellatelly, de Mark Mazower, de Christian Ingrao ou de Johann Chapoutot (qui fait le point sur les dernières recherches sur le nazisme dans Le nazisme, une idéologie en actes, collection Documentation photographique n°8085, Paris, La Documentation française, 2012). Parmi toutes ces parutions, peu étaient consacrées aux questions économiques, sauf l’ouvrage de Götz Aly (Comment Hitler a acheté les Allemands, Paris, Flammarion, 2005). Adam Tooze le souligne d’ailleurs, notant que l’histoire économique du nazisme a peu progressé ces vingt dernières années, à la différence de celles des rouages du régime, de la société et des politiques raciales par exemple. C’est pourquoi il se donne pour ambition « d’amorcer un processus de rattrapage intellectuel qui n’a que trop tardé » (p. 19), en nous livrant, sous l’égide de Marx, une imposante histoire économique de l’Allemagne nazie : « Le premier objectif de ce livre est donc de remettre l’économie au centre de notre intelligence du régime hitlérien... » (p. 20). Il se propose de le faire en rompant avec un postulat du XXe siècle, celui d’une supériorité économique particulière de l’Allemagne (encore présent dans les esprits de nos jours...), mythe détruit par les derniers travaux d’historiens de l’économie pour qui le fait économique majeur du XXe siècle est l’éclipse de l’Europe par de nouvelles puissances économiques, surtout les États-Unis. Dans les années 1930, l’Allemagne de Krupp, Siemens et IG Farben a un revenu national par tête dans la moyenne européenne (c’est-à-dire comparable en termes actuels à ceux de l’Iran ou l’Afrique du Sud), un niveau de consommation plus modeste que celui de ses voisins occidentaux, et « une société partiellement modernisée où plus de quinze millions d’habitants vivaient de l’artisanat traditionnel ou de l’agriculture paysanne. » (p. 21).

L’ennemi américain

La thèse centrale d’Adam Tooze s’appuie moins sur l’antiblchévique Mein Kampf (1924) que sur un manuscrit de Hitler connu sous le nom de « Second Livre », achevé pendant l’été 1928 et reprenant des discours de la campagne des législatives en Bavière en mai 1928, où se présentait Gustav Stresemann, ministre des Affaires étrangères de la République de Weimar. Convaincu que les États-Unis allaient devenir la force dominante de l’économie mondiale et un contrepoids de la Grande-Bretagne et de la France, Stresemann avait choisi, après la défaite de 1918, l’alliance financière américaine et l’intégration économique dans l’Europe capitaliste (les choix d’Adenauer après 1945), afin de gagner un marché assez vaste pour égaler les États-Unis. Pour Hitler, le moteur est la lutte pour des moyens de subsistance limités, autrement dit la colonisation d’un « espace vital » à l’Est, pour concurrencer la puissance des États-Unis dont l’hégémonie menacerait la survie économique de l’Europe et la survie raciale de l’Allemagne, es Juifs régnant tout autant à Washington qu’à Londres et Moscou. Hitler refuse « l’américanisation », l’adoption des modes de vie et de production des États-Unis car, derrière le libéralisme, le capitalisme et la démocratie se cache la « juiverie mondiale ».

Construire un complexe militaro-industriel

En somme, Hitler répond à une situation du XXe siècle par une solution du XIXe siècle. L’impérialisme, conjugué avec son idéologie antisémite, doit faire de l’Allemagne une puissance continentale capable de rivaliser avec l’Empire britannique mais surtout avec l’immense territoire des États-Unis. Dans ce but, Hitler organise à partir de 1933 le plus extraordinaire effort de redistribution jamais réalisé par un État capitaliste, puisque la part du produit national destinée à l’armée passe de moins de 1% à près de 20% en 1938, en même temps que la production industrielle augmente fortement, tout comme la consommation et l’investissement civil (6 millions de chômeurs étant mis au travail). Tout est sacrifié au réarmement et à la constitution de ce complexe militaro-industriel, particulièrement les intérêts des industries de biens de consommation et des paysans, d’où des mesures de rationnement des matières premières essentielles à partir de 1935 et plus tard le pillage de l’Europe. Cet effort supposait une forte organisation interne du régime et une très forte intervention de l’État dans l’économie, qui est acceptée par le grand capital allemand, affaibli par la crise de 1929, parce qu’elle était sélective, exploitant souvent l’initiative privée, et assurait des profits importants tout en maintenant l’ordre social et en écrasant la gauche et les syndicats. Enfin la conquête d’un Lebensraum à l’Est (avec le Generalplan Ost de rationalisation et de réorganisation agraire et le Plan de la faim de 1941 qui prévoyait de piller les ressources alimentaires d’une dizaine de millions de Polonais, de Russes et d’Ukrainiens) et la politique génocidaire, nées de l’idéologie raciale et antisémite, trouvaient leur justification économique au service de la puissance.

L’économie nazie et la Seconde Guerre mondiale

Pourtant Adam Tooze montre bien que la diplomatie, la planification militaire et la mobilisation économique ne se conjuguèrent pas en un plan de guerre cohérent et préparé à long terme. En septembre 1939, l’Allemagne se lance dans la guerre sans une forte supériorité matérielle ou technique sur la France, la Grande-Bretagne ou, en 1941, sur l’URSS. Avec une économie contrainte par les problèmes de la balance des paiements (impossible d’emprunter à la Grande-Bretagne et aux États-Unis ni de commercer avec eux) et sous contrôle administratif permanent, Hitler joue sans cesse contre la montre. En 1939, l’Allemagne ne peut plus accélérer son effort d’armement, quand la Grande-Bretagne, la France et l’URSS accélèrent leur réarmement. En outre, si en 1936 Hitler insiste encore sur le complot judéo-bolchévique, à partir de 1938 l’antisémitisme nazi opère un tournant antioccidental et particulièrement antiaméricain qui permet de mieux comprendre le Pacte germano-soviétique, qui de plus protégeait l’Allemagne contre un second front et contre les pires effets du blocus anglo-français. Outre les considérations idéologiques, face à l’ampleur de l’effort de guerre anglo-américain dès l’été 1940, les ressources économiques (céréales, pétrole) de l’URSS devenaient vitales pour la survie de l’Allemagne. Mais il fallait en même temps préparer l’invasion de l’URSS et répondre à la course aux armements transatlantique, ce qui nécessitait une victoire rapide contre l’Armée rouge, tout en conduisant les programmes SS de nettoyage ethnique génocidaire dans le cadre du Generalplan Ost.

Début 1942, les forces économiques et militaires mobilisées contre le IIIe Reich sont écrasantes. Mais le cœur du pouvoir politique nazi (le Gauleiter Sauckel, Herbert Backe l’orchestrateur du Plan de la faim, Göring, Himmler et Albert Speer) se lance alors dans un immense effort de mobilisation de toutes les ressources humaines (y compris la main d’oeuvre juive des camps), alimentaires et économiques (en pillant toute l’Europe) au service de la guerre et du « miracle des armements » de Speer. S’il y eu bien en 1944 une dernière accélération de la production allemande d’armements, ce fut au prix de la destruction d’une grande partie de l’Europe et de ses populations, et de l’Allemagne. Ainsi, en 1946, le PIB allemand par tête dépasse juste 2 200 dollars (niveau plus vu depuis les années 1880) et, dans les villes rasées, les rations alimentaires sont souvent inférieures à 1 000 calories par jour.

Un ouvrage majeur

On l’aura compris, on ne peut rendre compte ici de toute la richesse de cette fresque passionnante et tout à fait lisible par des non spécialistes d’histoire économique. Adam Tooze remet en cause bien des idées reçues sur les succès industriels du IIIe Reich et sur les motivations et les décisions nazies pendant la guerre, sans jamais sous-estimer l’importance des présupposés idéologiques nazis. Il nous propose une relecture brillante de la première moitié du XXe siècle, à la lumière des choix économiques opérés pour répondre aux bouleversements des équilibres économiques mondiaux, et nous offre un captivant plaidoyer pour l’histoire économique. Inutile de dire que, pour les professeurs d’Histoire de collège comme de lycée, c’est une lecture indispensable et particulièrement enrichissante, notamment en lycée pour les chapitres sur la croissance économique et la mondialisation, les totalitarismes et la guerre totale.

Source: La Cliothèque

http://clio-cr.clionautes.org/le-salaire-de-la-destruction-formation-et-ruine-de-l-economie-nazie.html

Paris, Les Belles Lettres, 2012, 812 p.

dimanche 3 mars 2013, par Laurent Gayme

Diplômé de King’s College et de la London School of Economics, Adam Tooze enseigne l’histoire de l’Allemagne à l’Université de Yale. Il a déjà publié Statistics and the German State, 1900-1945 : The Making of Modern Economic Knowledge, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 2001. Cet ouvrage est la traduction de son livre The Wages of Destruction : The Making and Breaking of the Nazi Economy, London, Allen Lane, 2006, récompensé la même année par le Wolfson History Prize et en 2007 par le Longman-History Today Book of the Year Prize.

Remettre l’histoire économique au centre

Il faut saluer cette traduction, que nous proposent Les Belles Lettres, d’un livre majeur. Le lecteur français a pu lire, ces dernières années, de nombreux ouvrages novateurs sur l’Allemagne nazie, qu’il s’agisse de ceux de Ian Kershaw, de Robert Gellatelly, de Mark Mazower, de Christian Ingrao ou de Johann Chapoutot (qui fait le point sur les dernières recherches sur le nazisme dans Le nazisme, une idéologie en actes, collection Documentation photographique n°8085, Paris, La Documentation française, 2012). Parmi toutes ces parutions, peu étaient consacrées aux questions économiques, sauf l’ouvrage de Götz Aly (Comment Hitler a acheté les Allemands, Paris, Flammarion, 2005). Adam Tooze le souligne d’ailleurs, notant que l’histoire économique du nazisme a peu progressé ces vingt dernières années, à la différence de celles des rouages du régime, de la société et des politiques raciales par exemple. C’est pourquoi il se donne pour ambition « d’amorcer un processus de rattrapage intellectuel qui n’a que trop tardé » (p. 19), en nous livrant, sous l’égide de Marx, une imposante histoire économique de l’Allemagne nazie : « Le premier objectif de ce livre est donc de remettre l’économie au centre de notre intelligence du régime hitlérien... » (p. 20). Il se propose de le faire en rompant avec un postulat du XXe siècle, celui d’une supériorité économique particulière de l’Allemagne (encore présent dans les esprits de nos jours...), mythe détruit par les derniers travaux d’historiens de l’économie pour qui le fait économique majeur du XXe siècle est l’éclipse de l’Europe par de nouvelles puissances économiques, surtout les États-Unis. Dans les années 1930, l’Allemagne de Krupp, Siemens et IG Farben a un revenu national par tête dans la moyenne européenne (c’est-à-dire comparable en termes actuels à ceux de l’Iran ou l’Afrique du Sud), un niveau de consommation plus modeste que celui de ses voisins occidentaux, et « une société partiellement modernisée où plus de quinze millions d’habitants vivaient de l’artisanat traditionnel ou de l’agriculture paysanne. » (p. 21).

L’ennemi américain

La thèse centrale d’Adam Tooze s’appuie moins sur l’antiblchévique Mein Kampf (1924) que sur un manuscrit de Hitler connu sous le nom de « Second Livre », achevé pendant l’été 1928 et reprenant des discours de la campagne des législatives en Bavière en mai 1928, où se présentait Gustav Stresemann, ministre des Affaires étrangères de la République de Weimar. Convaincu que les États-Unis allaient devenir la force dominante de l’économie mondiale et un contrepoids de la Grande-Bretagne et de la France, Stresemann avait choisi, après la défaite de 1918, l’alliance financière américaine et l’intégration économique dans l’Europe capitaliste (les choix d’Adenauer après 1945), afin de gagner un marché assez vaste pour égaler les États-Unis. Pour Hitler, le moteur est la lutte pour des moyens de subsistance limités, autrement dit la colonisation d’un « espace vital » à l’Est, pour concurrencer la puissance des États-Unis dont l’hégémonie menacerait la survie économique de l’Europe et la survie raciale de l’Allemagne, es Juifs régnant tout autant à Washington qu’à Londres et Moscou. Hitler refuse « l’américanisation », l’adoption des modes de vie et de production des États-Unis car, derrière le libéralisme, le capitalisme et la démocratie se cache la « juiverie mondiale ».

Construire un complexe militaro-industriel

En somme, Hitler répond à une situation du XXe siècle par une solution du XIXe siècle. L’impérialisme, conjugué avec son idéologie antisémite, doit faire de l’Allemagne une puissance continentale capable de rivaliser avec l’Empire britannique mais surtout avec l’immense territoire des États-Unis. Dans ce but, Hitler organise à partir de 1933 le plus extraordinaire effort de redistribution jamais réalisé par un État capitaliste, puisque la part du produit national destinée à l’armée passe de moins de 1% à près de 20% en 1938, en même temps que la production industrielle augmente fortement, tout comme la consommation et l’investissement civil (6 millions de chômeurs étant mis au travail). Tout est sacrifié au réarmement et à la constitution de ce complexe militaro-industriel, particulièrement les intérêts des industries de biens de consommation et des paysans, d’où des mesures de rationnement des matières premières essentielles à partir de 1935 et plus tard le pillage de l’Europe. Cet effort supposait une forte organisation interne du régime et une très forte intervention de l’État dans l’économie, qui est acceptée par le grand capital allemand, affaibli par la crise de 1929, parce qu’elle était sélective, exploitant souvent l’initiative privée, et assurait des profits importants tout en maintenant l’ordre social et en écrasant la gauche et les syndicats. Enfin la conquête d’un Lebensraum à l’Est (avec le Generalplan Ost de rationalisation et de réorganisation agraire et le Plan de la faim de 1941 qui prévoyait de piller les ressources alimentaires d’une dizaine de millions de Polonais, de Russes et d’Ukrainiens) et la politique génocidaire, nées de l’idéologie raciale et antisémite, trouvaient leur justification économique au service de la puissance.

L’économie nazie et la Seconde Guerre mondiale

Pourtant Adam Tooze montre bien que la diplomatie, la planification militaire et la mobilisation économique ne se conjuguèrent pas en un plan de guerre cohérent et préparé à long terme. En septembre 1939, l’Allemagne se lance dans la guerre sans une forte supériorité matérielle ou technique sur la France, la Grande-Bretagne ou, en 1941, sur l’URSS. Avec une économie contrainte par les problèmes de la balance des paiements (impossible d’emprunter à la Grande-Bretagne et aux États-Unis ni de commercer avec eux) et sous contrôle administratif permanent, Hitler joue sans cesse contre la montre. En 1939, l’Allemagne ne peut plus accélérer son effort d’armement, quand la Grande-Bretagne, la France et l’URSS accélèrent leur réarmement. En outre, si en 1936 Hitler insiste encore sur le complot judéo-bolchévique, à partir de 1938 l’antisémitisme nazi opère un tournant antioccidental et particulièrement antiaméricain qui permet de mieux comprendre le Pacte germano-soviétique, qui de plus protégeait l’Allemagne contre un second front et contre les pires effets du blocus anglo-français. Outre les considérations idéologiques, face à l’ampleur de l’effort de guerre anglo-américain dès l’été 1940, les ressources économiques (céréales, pétrole) de l’URSS devenaient vitales pour la survie de l’Allemagne. Mais il fallait en même temps préparer l’invasion de l’URSS et répondre à la course aux armements transatlantique, ce qui nécessitait une victoire rapide contre l’Armée rouge, tout en conduisant les programmes SS de nettoyage ethnique génocidaire dans le cadre du Generalplan Ost.

Début 1942, les forces économiques et militaires mobilisées contre le IIIe Reich sont écrasantes. Mais le cœur du pouvoir politique nazi (le Gauleiter Sauckel, Herbert Backe l’orchestrateur du Plan de la faim, Göring, Himmler et Albert Speer) se lance alors dans un immense effort de mobilisation de toutes les ressources humaines (y compris la main d’oeuvre juive des camps), alimentaires et économiques (en pillant toute l’Europe) au service de la guerre et du « miracle des armements » de Speer. S’il y eu bien en 1944 une dernière accélération de la production allemande d’armements, ce fut au prix de la destruction d’une grande partie de l’Europe et de ses populations, et de l’Allemagne. Ainsi, en 1946, le PIB allemand par tête dépasse juste 2 200 dollars (niveau plus vu depuis les années 1880) et, dans les villes rasées, les rations alimentaires sont souvent inférieures à 1 000 calories par jour.

Un ouvrage majeur

On l’aura compris, on ne peut rendre compte ici de toute la richesse de cette fresque passionnante et tout à fait lisible par des non spécialistes d’histoire économique. Adam Tooze remet en cause bien des idées reçues sur les succès industriels du IIIe Reich et sur les motivations et les décisions nazies pendant la guerre, sans jamais sous-estimer l’importance des présupposés idéologiques nazis. Il nous propose une relecture brillante de la première moitié du XXe siècle, à la lumière des choix économiques opérés pour répondre aux bouleversements des équilibres économiques mondiaux, et nous offre un captivant plaidoyer pour l’histoire économique. Inutile de dire que, pour les professeurs d’Histoire de collège comme de lycée, c’est une lecture indispensable et particulièrement enrichissante, notamment en lycée pour les chapitres sur la croissance économique et la mondialisation, les totalitarismes et la guerre totale.

Source: La Cliothèque

http://clio-cr.clionautes.org/le-salaire-de-la-destruction-formation-et-ruine-de-l-economie-nazie.html

Thursday, January 21, 2016

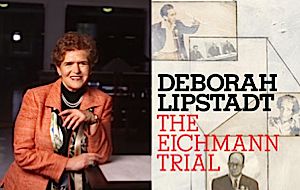

Arendt on Trial. New Book About Eichmann Trial Challenges Hannah Arendt's Criticism of Jewish Council

Arendt on Trial

Arendt on TrialMichelle SieffMarch 14, 2011Image: Nextbook/Schoken

The Eichmann Trial

By Deborah Lipstadt

Nextbook/Schocken, 272 pages, $24.95

In 1961, the young state of Israel tried and executed the Nazi war criminal Adolf Eichmann. Hannah Arendt covered the trial for the New Yorker, an account that was published in 1963 as “Eichmann in Jerusalem.” Arendt did not set out to write a journalistic trial narrative. Instead, she articulated a series of provocative and critical judgments about the trial, the wartime role of Europe’s Jewish Councils (the infamous Judenrats) and Eichmann’s motives. The book ignited a firestorm of controversy that, 50 years later, still crackles. Her book remains the lens through which people view the Eichmann trial.

Challenging Arendt: Deborah Lipstadt, the author of ?The Eichmann Trial.?

Image: Nextbook/Schoken

Challenging Arendt: Deborah Lipstadt, the author of ?The Eichmann Trial.?

With her new book, “The Eichmann Trial,” historian Deborah Lipstadt attempts to refute Arendt’s main arguments. On the cover is an iconic image of Arendt — pearl-bedecked and pensive, a cigarette dangling from her fingers — and an entire chapter of the book discusses her arguments. Although other scholars have re-examined the Eichmann trial — most notably the Israeli historian Hannah Yablonka, in a book published in English in 2004 as “The State of Israel vs. Adolf Eichmann” — Lipstadt aims to reach a wider audience.

Especially when compared to Arendt, who was more concerned with the whys and wherefores than the whats, Lipstadt has written a reliable guide to the basic facts of the trial. Lipstadt succinctly describes the key events in chronological order: Israel’s abduction of Eichmann in Argentina; the selection of the prosecutor, defense attorney and judges; the media response to the trial; the prosecutor’s chilling opening statement; the testimony of the survivor witnesses; Eichmann’s testimony; the judgment and the impassioned debate over the death sentence.

Arendt bitterly criticized the Jewish Councils for helping the Nazis compile lists of Jews to be deported. This observation was the one that sparked the violent outrage in American Jewish circles because of her insinuation that the Nazi authorities and Jewish Councils were equally culpable. Lipstadt vehemently challenges Arendt’s argument, noting that the Einsatzgruppen murdered thousands of Jews in the Soviet territories, which had no Jewish Councils. In her mind, this proves that Arendt exaggerated the importance of the Jewish Councils.

True. But Lipstadt has the advantage of 50 years of historical research, much of which was spurred by Arendt’s provocative argument. And, ironically, Lipstadt’s narrative ultimately persuades me that Arendt’s spotlight on the actions of the Jewish Councils was justified at the time. Lipstadt vividly describes how, during the testimony of a Hungarian Jewish Council member, Pinchas Freudinger, a spectator began shouting and accused Freudinger of being responsible for the death of his family. It was a Holocaust victim in the courtroom who accused the Jewish Councils of moral culpability. Arendt’s contribution was to analyze a complicated moral issue — raised by a Holocaust victim at the trial — with her characteristic erudition, seriousness and fearlessness.

Arendt’s book is most notorious for its portrait of Eichmann’s motives. Based on her analysis of his statements and testimony, Arendt contended that Eichmann was not motivated by a fanatical hatred of Jews. Other than a desire to advance his career and obey his superiors, he had no real motives at all, she maintained. Arendt concluded that Eichmann’s “sheer thoughtlessness” revealed the “banality of evil.”

Lipstadt argues that, to the contrary, Eichmann was a committed anti-Semite. Sometimes Lipstadt’s prose has the whiff of a dogmatic rant; but she also marshals some compelling evidence, some of which was not part of the trial and hence not available to Arendt. She points to Eichmann’s speech to his men, in which he declared he would go to his grave fulfilled because he had murdered millions of Jews. Lipstadt also invokes as evidence a memoir written by Eichmann during the trial, which was sealed in Israel’s archives but released to assist Lipstadt in her own trial in 2000 against Holocaust denier David Irving.

Though she doesn’t provide details, Lipstadt contends that the memoir proves that Arendt “was just plain wrong about Eichmann.” In a fascinating description of Judge Benjamin Halevi’s questioning of Eichmann, she also recounts how Eichmann compromised his defense that he was just following orders by admitting he exempted several Jews from deportation.

Even if Lipstadt is correct about Eichmann — and in his 2004 biography of Eichmann, historian David Cesarani precisely documented Eichmann’s anti-Semitism — Arendt was still onto an important idea. The bloody post-Holocaust history of genocides provides ample evidence of the “banality of evil.” Some very chilling evidence appears in the book “Machete Season,” by French journalist Jean Hatzfeld. Hatzfeld conducted extended interviews with a group of imprisoned Rwandan genocidaires. Throughout the book, they speak of the killing as a business and a job, without any reference to moral considerations.

In her conclusion, Lipstadt argues that the decision by the prosecutor, Attorney General Gideon Hausner, to include survivor testimonies, despite no direct legal need for it, was the most important aspect of the trial. Drawing on the empirical work of other scholars, she argues that, by allowing victims to tell their stories publicly, the trial changed the perception and status of Holocaust victims in Israeli society. In Lipstadt’s mind, this was the trial’s greatest legacy. Her conclusion also challenges an Arendtian judgment. Arendt had criticized Hausner for injecting political goals into the trial. She specifically criticized the focus on Jewish suffering and the victim testimonies: “For this case was built on what the Jews had suffered, not on what Eichmann had done,” she lamented.

Arendt’s view was based on a doctrine — which she made explicit — about the purpose of trials, even trials of war criminals. “The purpose of a trial is to render justice, and nothing else,” she maintained. By defending the trial on the grounds that it integrated victims into Israeli society, Lipstadt assumes that war crimes trials can and should further more expansive goals, such as the political objective of nation-building. Since the Eichmann trial, in the wake of the bloody conflicts of the 1990s, war crimes trials have proliferated. Modern human rights groups have defended these trials on the grounds that they further classic political goals, such as peace and democratic consolidation.

Our contemporary discussions about what law scholar Ruti Teitel named “transitional justice” are often muddled, because there is little explicit philosophical debate — let alone consensus — about the appropriate goals and standards by which such trials should be assessed. This conceptual miasma might be one reason there are so few empirical studies on the impact of war crimes trials. This is a shame, since these trials are a tremendous experiment in virtuous politics. Arendt criticized the Eichmann trial because it injected politics into law. By defending the trial because of its political consequences, Lipstadt lays out an alternative doctrine. Who’s right? For anyone concerned about the legacy of Eichmann and the future of war crimes trials, it’s an essential question.

Michelle Sieff is a research fellow at the Yale Initiative for the Study of Antisemitism.

Source: Forward/Haaretz

http://forward.com/culture/136127/arendt-on-trial/

http://www.haaretz.com/jewish/new-book-about-eichmann-trial-challenges-hannah-arendt-s-criticism-of-jewish-council-1.349203

Tuesday, January 19, 2016

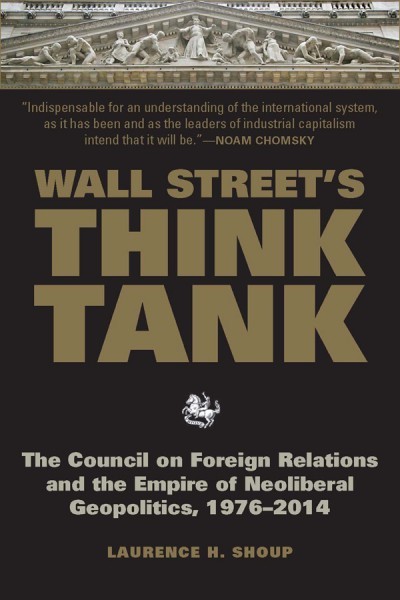

Wall Street’s Think Tank: The Council on Foreign Relations and the Empire of Neoliberal Geopolitics, 1976-2014

Wall Street’s Think Tank: The Council on Foreign Relations and the Empire of Neoliberal Geopolitics, 1976-2014

by Laurence H. Shoup

The Council on Foreign Relations is the most influential foreign-policy think tank in the United States, claiming among its members a high percentage of government officials, media figures, and establishment elite. For decades it kept a low profile even while it shaped policy, advised presidents, and helped shore up U.S. hegemony following the Second World War. In 1977, Laurence H. Shoup and William Minter published the first in-depth study of the CFR, Imperial Brain Trust, an explosive work that traced the activities and influence of the CFR from its origins in the 1920s through the Cold War.